Movement of the People by Mary N. Taylor

Author:Mary N. Taylor [Taylor, Mary N.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780253057839

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: Indiana University Press

Published: 2021-08-31T00:00:00+00:00

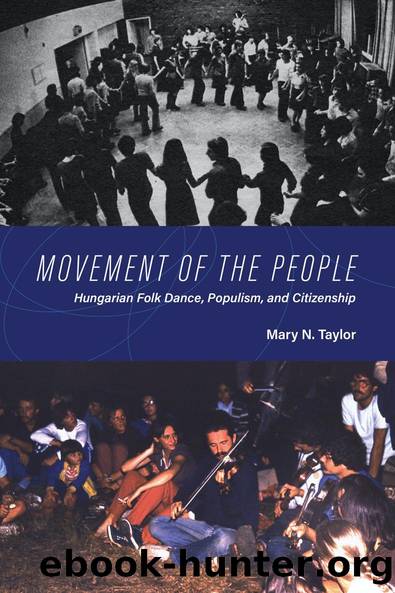

Fig. 5.1 Revivalists practicing at camp in Szék (Sic), Transylvania, 2004. Hi8 video still by the author.

The following section explores the specific practices and forms that make up folk dance as mother tongue and factors contributing to their interpretation. I describe what happens when communicative technologies are abstracted according to revivalist ideologies and institutional arrangements focused on the perpetuation of authentic Hungarian practices. I focus particularly on dance/music forms, etiquette, conversation, and place-based tourism. Drawing on the well-examined example of gender relations in the dance to illustrate the relationship of dance event practices and socialization, I point to what other kinds of socialization may be at hand, particularly as connected to place, territory, and the content and scale of the nation.

SPATIOTEMPORAL FORMS: MATERIAL PRACTICES IN TÃNCHÃZ

Táncház events are structured around dance cycles, or suites: relatively fixed sets of dances in a certain order that coordinate with a musical suite. Each cycle is adopted from a particular village or region. Once the band begins to play, experienced táncház goers are both aware of and authorial of what dance âshouldâ and will follow. Upon hearing the music, we are able to determine the village or region from which it originates and can thus author dances within the genre of that locale. Familiarity with a broad repertoire of regional dance forms has been peculiar to revivalists, as villagers have tended until recently to know only local dances (Halmos 2000, 31).25 For táncház participants, along with a growing proportion of revivalist villagers, a ânationalâ patrimony is available from which specific regional variants of âHungarian danceâ can be identified. Each dance cycle can be placed at a particular place on the map of Greater Hungary. The fact that an overwhelming percentage of the dances/dance cycles encountered in táncház today are Transylvanian in origin has important implications for collective memory.26

Reflecting the geography of uneven development, the majority of communities practicing Hungarian folk dance as social dance in the 1970s were located in Transylvania. As we have seen, the history of ethnography, and the combination of népi and Christian National practices and ideologies in the interwar and World War II periods, made Transylvania the focus of collection and authenticity. This process of nationalization of local traditions, mostly from Transylvania, has a few important effects: it abstracts each âlocal traditionâ into the category âHungarianâ and widens the practice of each to all Hungarians, and it cements the identification of specific dances with specific villages or regions, establishing them as sources of authenticity. Furthermore, it associates Hungarian culture with Transylvanian villages. The revival of village practices in táncház also serves to make folk dance static or timeless (see Livingston 1999, 69). Because revival has stopped the clock, it is not the contemporary practices of the folk that are the source of folk culture but rather the practices of the parents and grandparents of rural folkâexhibited by the elderly or captured on film, sound recordings, and photographsâand accounts and practices of ethnographers and revivalists. While studies show that the dances

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

A Company of Swans by Eva Ibbotson(712)

Dance! by Dr. Ann Stevenson(650)

Spider Dance(602)

The Pilates Effect by Stacey Redfield(513)

A Pictorial History of Horror Movies by Dennis Gifford(505)

Be With by Forrest Gander(501)

Beginning Modern Dance by Miriam Giguere(486)

Stripped by Barton Bernadette;(478)

Eurythmy by Thomas Poplawski(478)

THE COLLABORATIVE HABIT by TWYLA THARP & Jesse Kornbluth(464)

Bruno My Story by Tonioli Bruno(446)

Dance Technique and Injury Prevention by Howse Justin; Hancock Shirley; Hancock Shirley(439)

Democracy's Body: Judson Dance Theater, 1962-1964 by Sally Banes(423)

The Creative Screenwriter: 12 Rules to Follow—and Break—to Unlock Your Screenwriting Potential by Hoxter Julian(423)

Dancing Out of the Closet by Matthew Shaffer(415)

The Dancer's Way by Linda H. Hamilton Ph.D(395)

Pina Bausch - The Biography by Marion Meyer Penny Black(382)

Until the Lions by Karthika Nair(344)

Dancing Deeper Still: The Practice of Contact Improvisation by Martin Keogh(317)